Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A New History of the New World

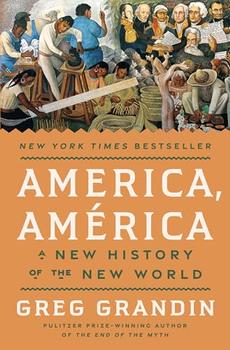

by Greg Grandin

He was gone for two years, returning to the Caribbean in 1509, and in his later writings was circumspect about his own service to the Conquest. He accompanied at least one incursion into Hispaniola's western lands, provisioning troops with supplies but also perhaps lending a hand to put down Indians with sword and harquebus. Christopher Columbus's son, Diego Colón, Hispaniola's governor, granted him an encomienda, or consignment of Indian laborers, on the north coast of the island in the Cibao Valley.

The term encomienda refers to a kind of slavery, but indios encomendados, or commended Indians, weren't considered private property, or chattel. Rather, they were formally something like wards, members of an existing village or community, who, in exchange for labor, were to receive instruction in Christian doctrine from their overlords, their guardian encomenderos. The encomienda was important, but it was just one of many coerced labor systems. There was out-and-out enslavement, of Native Americans and Africans; there were onerous tribute demands and a labor corvée called the repartimiento. The "Conquest brought about so many forms of Indian servitude," wrote one historian in the early 1900s, "that it is very difficult to master the nature of them all, and to follow them into all their minute details."

Las Casas's conversion was slow in coming, and can be dated to 1512, when he accompanied Captain Pánfilo de Narváez on an expedition to pacify Cuba. He went as a priest, and was horrified as the campaign turned into, as one historian writes, "an odyssey of pillage and plunder, of death and destruction." Massacre followed massacre, until Narváez's men arrived at the last unconquered village, Caonao. There, the soldiers were greeted at dawn by thousands of kneeling Indians, who bowed their heads as Narváez's mounted men took their place in the plaza. The tension Las Casas sets up, as he later reflected on the day's events, between motion and stillness is stunning. The Indians kneel quietly. The horses tower over them. All is quiet except for the shuffle of hooves, as the mounts shift the weight of their riders and their heavy armor. No provocation on the part of the town's inhabitants interrupts the tense calm. Then, suddenly, a soldier unsheathes his sword and starts slashing at those kneeling below him. The rest of Narváez's men join in, killing men, women, children, the sick and the old. They use lances to disembowel victims.

Narváez himself, Las Casas writes, sat calm amid the chaos "as if he were made of marble."

One villager, his intestines spilling out of his stomach, fell into Las Casas arms. The dichotomy in Las Casas's narration is now birth and death, being and nothingness: Las Casas baptized the man and performed last rites in the same breath. After the slaughter was over and the killers had moved on, Las Casas stayed behind to tend to the injured. He cleaned bandages, cauterized wounds, and tried to find some rational explanation for the carnage. He couldn't. The Spanish assault on Cuba, he said, was "a human disaster without precedent: the land, covered in bodies."

Still, though, he remained silent and accepted a second encomienda for his service on Narváez's campaign. This one, on the southern coast of Cuba, was made up of inhabitants from the village of Canarreo, which sat on the banks of the Arimao River. Las Casas lived there as a merchant priest, in a large, comfortable house built by his Indians. He said Mass in a small chapel and became wealthy. He couldn't, though, shake off the feeling that he was living in sin, violating the commandment not to steal.

Then, in preparation for a sermon to preach on Pentecostal Sunday in 1514, Las Casas, now thirty years old, came upon this sentence from Ecclesiastes: "To take a fellow-man's livelihood is to kill him, to deprive a worker of his wages is to shed blood." No scales fell from his eyes, no repulsion at witnessing babies being torn apart by dogs awakened his consciousness. Rather he simply reflected quietly on these words from Ecclesiastes and then made a decision to change his life. He abandoned his encomiendas, gave away his riches, and began a life of mendicant poverty and humanist advocacy.

Excerpted from America, América by Greg Grandin. Copyright © 2025 by Greg Grandin. Excerpted by permission of Penguin Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A book may be compared to your neighbor...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.