Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

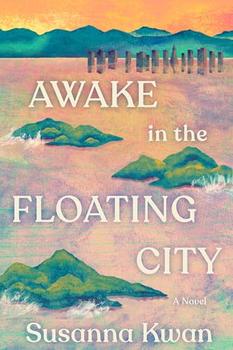

A Novel

by Susanna Kwan

Bo had stayed with Ricardo until his body had given up. She'd waited until the mortuary service had collected him for water cremation before going to the clay fridge, as he had directed, and locating his will, sealed in a plastic bag, deeding his remaining accounts to her. Not surprising, since he had long been alone, but she was neither family nor friend—just contracted labor.

It was enough to live on for a year, or several if she was frugal. This was what she'd hoped for since she was twenty: the money meant she didn't need to find a new gig—she could simply paint. But she'd found that she struggled to create with that freedom; something had changed, requiring effort she didn't know how to expend. She worked dutifully, made aimless, soulless marks while she awaited that elusive spark. As the months passed, her patience frayed and panic surfaced, coating her eyes and skin and everything she touched with a film of failure. She'd made a mistake. Her mother was right: she'd been given a gift but had wasted it. Clinging to the belief that there was meaning in the work, she'd insisted on staying to see it through. Then came the storm surge, then the long stillness that followed. The money shrank. The rain kept on.

She left the old woman's note on the floor and attended to the plan ahead. She packed some clothes, set her suitcase by the door, and waited for the day when she would walk down to the dock. The note tugged at her like a magnet, but she tried to forget it. Two or three days passed, maybe another.

The idle, fearful years had made her mind loose. Without schedule or focus, the hours had scattered. Her grasp of time had dimmed; she'd lost all sense of how the day passed outside her apartment. She had the feeling that life was spinning away from her on a widening orbit.

As a child she'd noticed that each day followed the one before, like breaths. Her mother had hung two clocks in their home—buy one, get one—the first over the mantel of a fireplace that didn't work and the other in the bathroom as a reminder to keep their showers brief. From the table where she ate, studied, and drew, Bo could hear both as they marked the seconds, just a hair from synchronization, pushing time forward like a damaged metronome, drawing her attention to her own heartbeat as it picked up speed and turned into a forceful knocking rhythm that drowned out the clocks.

Now she sensed the days going by through slivers and swatches of light moving between the leaves that had draped her window ever since she'd stopped cutting back the vines. She sustained a vague memory of the satisfaction of operating on scripted time.

A former painting teacher of hers, a widow, reported in a letter that her own dark period had lasted more than three years after her beloved had died. Three years before she could detect tamarind in a marinade or eat with any pleasure. Three years in which she declined to trim her nails, instead either growing them into talons or chewing them down. The black dog—that was what she called it.

It didn't help that the cycle of a year had distorted into a single interminable season.

In the early days of rain, every change had stood out. Bo had been new to the building then, drawn in by the low rent and central location after almost eight years on the west side in a poorly maintained live-work studio that she'd outgrown but hadn't known how to leave until it was condemned, the decision made for her. From her new apartment, she anxiously watched the city transform into something unrecognizable—unfathomable, at first, when for years they had known only drought and the threat of more drought. She drew daily, capturing the details, still believing the rain would end soon. Ceramic water-storage tanks filled and overflowed. Black rubber irrigation snakes secured to the perimeter of rooftop garden plots swelled and split. Farmers tried to adapt, sowing and harvesting according to this swing in the weather. Food supplies became unpredictable. People were robbed of their groceries. Sinkholes opened, like the neighborhood's collective hunger on display in the street. Mouths to swallow a city up. Inside, thick runoff stained the walls and left deposits. Streaks of copper ran down sodden curtains. She woke to putrid smells carried up through the vents from the boiler room, the basement, the street: skunk, mold, sewage, fermenting garbage. The green that blanketed the city drank up the water on its millions of fingers, and what wasn't absorbed poured down and ran into the gutters. She stopped running into other tenants on her floor and realized that most of the units had gone vacant. She watched as residents began to flee, the first of many waves of exodus, and still, the looping footage of floods on the news shocked her, no matter that she'd seen those very scenes on her own block.

Excerpted from Awake in the Floating City by Susanna Kwan. Copyright © 2025 by Susanna Kwan. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The dirtiest book of all is the expurgated book

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.