Chapter 1

Teresa

Milan and Florence

1929-1938

Teresa Mattei was eight when she slipped behind the curtain of the dark paneled confessional booth for her First Penance. She knelt and craned her neck upward, directing her girlhood indiscretions through the lattice to the priest waiting behind the curtain on the other side. The layers of thick fabric and rich wood were intended for anonymity between parishioner and priest. To atone for whatever she admitted that day, the priest prescribed three Hail Marys to the Pope.

Teresa responded, "Ma il Papa e un porco!"-"But the Pope is a pig!"

The priest jumped out of the confessional booth and pulled back the curtain on the other side.

"Who told you such nonsense?" he demanded of the dark-eyed little girl.

"I don't believe in you," Teresa responded defiantly; she had been taught since she was young about the dangerous friendship of the Pope and Mussolini. "I believe in my father."

Perhaps it is telling that Teresa was born in February 1921-just months before Benito Mussolini first held political office. She was the oldest daughter and middle of seven children, born to a Catholic father and a Jewish mother whose family had escaped a pogrom in Lithuania. Teresa spent most of her earliest childhood in the countryside outside of Milan, where her father had helped found one of Italy's first telephone companies. Milan was an industrial hub. It was also the cradle of Fascism, and the Mattei family had a front-row seat to its beginnings.

Her father, Ugo, had felt disdain for Mussolini since those earliest days of his political ambition. Ugo's company was slowly rolling out Italy's first private telephone lines around Milan and received an urgent request for one from Mussolini's newspaper office, declaring a need to be in constant touch with Rome. But Ugo held the position that the newspaper would not be able to jump the line.

One day, Mussolini showed up at Ugo's office in person and demanded special service.

Ugo refused, and Benito's infamous temper flared. He threatened a press campaign against Ugo and his company.

"And I will smash your head," Ugo countered. Calmly, he reached for the inert grenade that he kept on his desk as a personal reminder of the horrors of war, and cocked his arm. Mussolini ran out of his office, never to return.

Teresa had grown up hearing this tale, and many others. "My father always maintained that Mussolini was a great coward and that a thousand people in Italy would have been enough to chase him away," she said.

Decades earlier, during World War I, Ugo, a decorated naval captain, had an epiphany hiding under an armored car belonging to the enemy. As he had told the story to Teresa and her siblings, he was trapped there for hours, forced to watch the terror of battle around him. While he, helpless beneath the vehicle, witnessed so many men slaughter one another, he got to know his surroundings well, his senses sharpened, perhaps, by the proximity of death. He noticed for the first time that the tires of this enemy car were made by the Italian company Pirelli. Italian businessmen had supplied both sides of the conflict, profiting double. He had walked away from the battlefield a pacifist, telling Teresa he had come to understand that "wars are only for the convenience of a few." Ugo would spend the following decades using what power he had to resist the oppression of Fascism, and then the threat of war.

Ugo had followed the trajectory of Benito Mussolini since he began his career in media. Benito was not much older than Ugo, but his upbringing was far less comfortable. His mother was a schoolteacher and his father a blacksmith and Socialist journalist who often frittered away the family finances. As a young man, Benito became known as an instigator and gifted speaker, and found himself drawn to revolutionary politics, in 1912 landing a job at the helm of Italy's official Socialist newspaper, Avanti!, where he quickly doubled its circulation and vociferously opposed war.

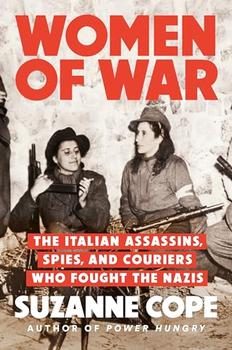

Excerpted from Women of War by Suzanne Cope. Copyright © 2025 by Suzanne Cope. Excerpted by permission of Dutton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.